“Wild plants have managed to protect themselves from pests and diseases for countless generations,” says Wanda Huang, a foremost foraging expert in Hong Kong.

“They’ve evolved over thousands, even millions of years… so when we eat something from the wild, we’re taking all that in.”

Huang is descended from five generations of Chinese herbalists on her father’s side, and she brings an encyclopaedic knowledge of wild edibles. As a young girl, she was taught how to forage by her father and grandfather on China’s untamed hillsides, and continues to forage in Hong Kong today.

“I am not trained as a botanist, but I want to do my part to preserve and pass on this ancestral knowledge,” she says. Prior to the pandemic, the Canadian-Chinese educator and conservationist regularly led guided foraging expeditions in the Hong Kong countryside, sharing her knowledge with curious observers.

For instance, she explains: dandelions are a wild form of lettuce that have not been widely domesticated by humans. Yet the plant contains substantially more vitamin C, A, and K than a standard head of grocery store lettuce, its commonly cultivated cousin. It’s virtually indestructible and relentlessly persistent; even a small piece of root left in the ground can regenerate and shoot back up. “You can imagine the wonderful nutrients it carries,” she asserts.

Huang is one of a handful of proponents leading Hong Kong’s blossoming foraging movement. Long practised by elderly aunties, today it’s become more mainstream, embraced by everyone from nature enthusiasts and daytrippers to the city’s top restaurants and bars.

What is foraging?

Foraging, also known as wildcrafting, is the act of gathering wild plants for free. In a city renowned for its verdant forests – around 75 percent of Hong Kong is green countryside – it offers ample natural resources for the savvy scavenger. But it’s not as simple as just hitting the trails and picking your haul.

To start with, plants and trees that grow in urban areas are often sprayed heavily with insecticides. So, while pruning mystery berries or plucking a furry mushroom on a well-worn path may sound idyllic, you risk poisoning yourself – or worse.

It’s also illegal to dig up plants – including algae, lichens and fungi – from private land without permission from the landowner or occupier. Some species are specially protected against picking, uprooting, damage and sale. According to the Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department, foraging in country parks is also prohibited by law.

It can be tricky to find your footing when it comes to this road less travelled. That’s why people like Huang are essential to learning the ropes. She says there are two options for finding clean and obtainable plants in Hong Kong: abandoned farmlands and local organic farms.

“People can be quite sensitive even if the farmland appears abandoned. I’ve been scolded before by landowners,” she cautions. “That’s why I prefer to work closely with an organic farm and get their permission.”

Organic farms and foraging

The farms in Hong Kong that Huang visits tend to use only a part of their land for organic agriculture, because it encourages beneficial insects and leaves adequate space for crop rotation. The biggest farm she works with is Yi O, a cooperative organic farm located about five minutes by boat away from Tai O. She says they have 11 hectares of land, but only cultivate three of them, leaving eight wild hectares for Huang to roam around for ingredients.

In a city that imports over 90 percent of its produce, primarily from mainland China, foraged goods from organic farmland reflects a very

different, and far more conscious, approach to food appreciation. No surprise then, that Huang has connected some of the city’s most popular F&B establishments with organic farmers, helping them to sell their produce – which they may consider no more than pesky weeds – at fair prices.

“COVID-19 gave us a chance to slow down and better understand what surrounds us – local flavours, markets and producers,” says Simone Rossi, Director of Bars at Rosewood Hong Kong. “People are starting to open their eyes to what can be found in their own backyard, instead of what can be shipped across the border.”

Last year, the hotel’s award-winning cocktail lounge, DarkSide, partnered with spirits brand Fernet Hunter as well as Huang, to create their own locally sourced amaro – an herbal liqueur – using foraged ingredients.

“The goal with the Hong Kong amaro was to have a very bright and fresh style with subtle bitter notes that expresses a local terroir,” says Rossi. “The final blend of botanicals includes bur-marigold leaves, Chinese mugwort, citron leaves, Cuban oregano, wild ginger seeds and leaves, calamansi, calamondin, Lantana flowers and leaves, pomelo leaves and wild Chinese peppercorns. We crafted something that celebrates the city’s rich culture and flavours.”

Local craft brewery Yardley Brothers also released a limited edition sour beer featuring foraged fruit: the native wampi. A distant relative of citrus renowned in Chinese medicine for aiding digestion and reducing inflammation, the sweet-sour tree fruit grows extensively in southern China and parts of southeast Asia.

“We like to push the limits of brewing craft beers by using new and rare fruits,” says Yardley Brothers’ Terence Yiu. “We want to showcase the different possibilities of beer.”

The Kwai Chung-based brewery worked with residents in Mo Tat Wan, a small village on the southern side of Lamma Island, to forage 100 kilos of wild wampi from the community’s surrounding wildland. Then, they hand- squeezed the fruit, before hopping it to create the Foraged Sour: a mouth-puckeringly tart brew with notes of tamarind, dried plum and fennel.

The amplified tasting notes of untame ingredients – often bitter, sour and astringent – may challenge less experimental palates, but they’ve become highly prized by discerning tastemakers.

Nana Chan is the founder of artisanal tea brand Plantation. She says that wild-grown teas, lauded for their full- flavoured infusions, are a sought-after commodity with tea-lovers, too. “Wild teas must struggle to survive and have had time to crossbreed. In contrast, most cultivated teas are selected and developed by humans,” she explains.

Five-star hotels including the Mandarin Oriental, Island Shangri-La and Four Seasons have also been known to reach for seasonal wild produce to add complexity and a local infusion to their menus.

The modern foraging landscape

Huang estimates there are about 3,000 varieties of plants in Hong Kong. A handful are poisonous, while many more have different degrees of toxicity. Plenty, however, are just plain delicious and nutrient-dense.

The evergreen prickly ash, for example, evokes the numbing Sichuan peppercorn, doused in zesty lime. Shell ginger leaves make aromatic wrappers for Chinese dumplings. Malabar spinach offers twice as much vitamin A as kale, and is abundant in vitamin C, iron, calcium, and potassium. Wood sorrel plants offer a mildly sour taste, while the savoury pods of the mimosa bean go a long way in livening up curries. Bur-marigold, one of the botanicals used in DarkSide’s amaro, adds depth to stir-frys, soups, even a humble plate of scrambled eggs.

Huang points out that foraged greens, herbs and flowers have been a part of Asian culture for many generations, used in everything from teas and tinctures to medicinal infusions. “People in rural parts of Thailand and China routinely eat wild vegetables, but there’s no glamorisation in the media,” she says. “It’s only in the last five or six years that foraging has become trendy in the west.”

She warns, however, that there’s a growing belief among local foragers that store-bought produce – sweeter in taste and larger in size – is superior to wild ingredients. Huang describes it as an internalised stigma that she’s afraid will affect the practice’s future. “Many heritage foragers in the community, particularly elders in Fanling and northern parts of the New Territories, do not consider their own wisdom sacred,” she says.

How to get involved

For those adventurous and open-minded enough, Huang says that foraging offers myriad benefits, from innovative flavours to a potent payload of vitamins and minerals. There’s also the opportunity to reconnect with nature, explore the wild frontiers of Hong Kong, and the surprising gratification that comes with plucking your next meal from the earth.

What’s the easiest way to get started on your foraging journey? Supporting Hong Kong’s organic producers goes a long way, by keeping swathes of the city’s vast wilderness free, unfarmed, and open to the city’s foraging community.

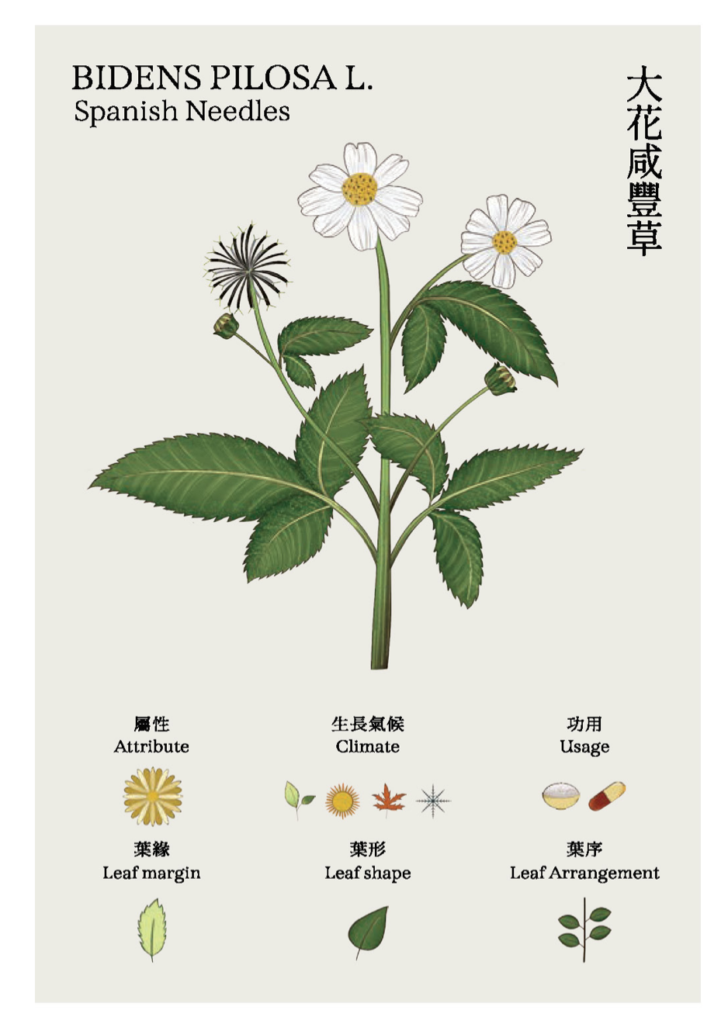

Some local resources also exist for the studious forager. Oil Street Art Space, a public art space overseen by LCSD, released a set of 20 illustrated cards featuring the city’s most common edible weeds. “We designed

and launched our ‘Yeah Veggie’ cards to encourage the public to reflect on food justice principles, and learn more about wild plants,” a representative from Hong Kong’s Art Promotion Office said.

The cardinal rule for foraging: never start solo! It’s essential to begin by partnering up with a local expert, who is able to teach you best practices while also keeping you safe.

“Foraging should be carried out responsibly,” advises Rossi from Rosewood Hong Kong. “You need to know what you’re looking for and be cautious of over-foraging. Go with a local expert who will make sure you don’t miss out on any of the good stuff.”

According to Huang, the following organisations offer semi-regular foraging workshops in Hong Kong: Yi O Farm, A-Team Edventures and Hong Kong Gardening Society.

Read more about Hong Kong’s nature experiences on Liv: Forest Bathing in Hong Kong