Hong Kong has been plagued with water safety scandals over the past 12 months. From elevated lead levels in public housing estates to legionella outbreaks and carcinogens in our reservoirs, many of us are exploring how we can safeguard our water supply. So what’s the story with Hong Kong’s water, and what kind of filter should we buy to protect ourselves? By Gayatri Bhaumik

Is our water safe?

Between 70 and 80 percent of Hong Kong’s fresh water comes from Dongjiang, in China’s Guangdong Province; the remainder comes from rainwater. Treatment at one of 21 pumping stations makes the water safe to drink; after filtering, chlorine is added to protect us from bacteria and parasites and to safeguard the water en route to our taps. Chlorine is easily removed by boiling or allowing the water to stand for an hour or so before drinking. Once the water leaves the mains, however, water safety is no longer guaranteed by the government, and it can become contaminated by dirty water tanks, old pipes and poorly maintained taps, all of which are the responsibility of building management or apartment owners.

What contaminants do I need to look out for?

Lead is the main concern right now, and while excessive exposure can cause serious health issues, contamination is more common from sources other than water, such as industrial workplaces, paint or leaded petrol. “Lead exposure arises from a range of sources, of which water is frequently a minor one”, says Alexander von Hildebrand, a WHO Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Program Manager. Water can also contain iron rust, sand, arsenic and nitrates, among other contaminants. But it’s important to be practical about the risks. “All sources of drinking water can contain some contaminants”, says Richard Andrews, Director of Global Business Development for NSF International, the global public health and safety organisation responsible for developing health standards and certification programs for the world’s food, water, consumer products and environment. “At low levels, most of these contaminants are not considered to be harmful”.

What can I do?

Check whether your building is certified by the Water Supply Department’s Quality Water Supply Scheme for Buildings, a voluntary scheme that regularly assesses a building’s water supply with inspections of plumbing systems and water tanks, and testing of water samples. If it is, you can safely drink from the tap. For $250, you can also check the lead content of your water supply at the Hong Kong Standards and Testing Centre. But the easiest way to ensure that your water is safe is to have a water treatment system at home.

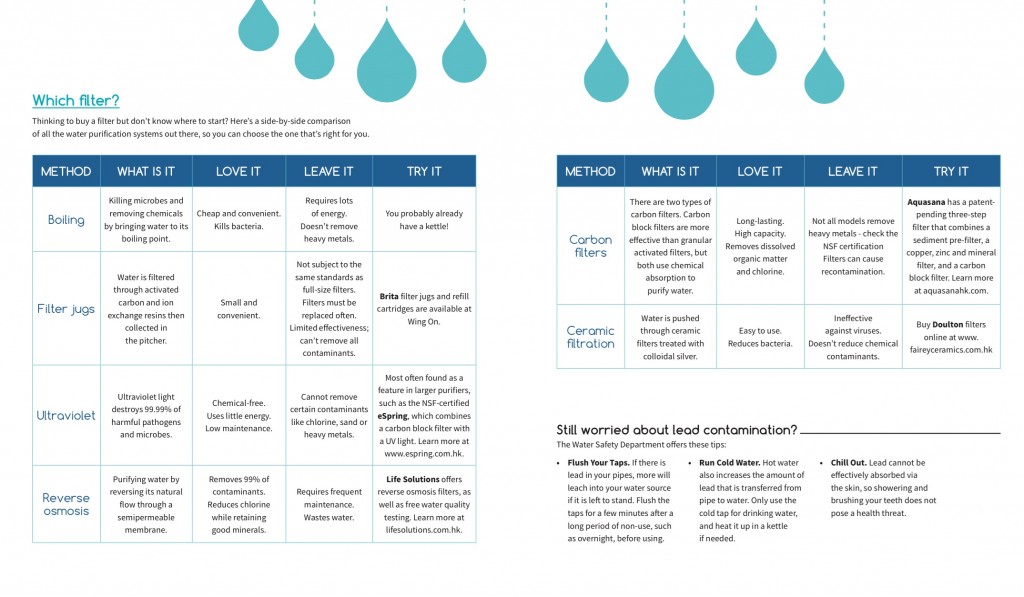

How to choose a purification system

- Consider which contaminants you’re concerned about. “Not all water filters are effective for reducing all contaminants”, warns Andrews. The NSF website has information about which systems work best on which contaminants.

- Decide what product suits your needs. Point-of-entry systems treat the water entering a home, while point-of-use systems – like tap or counter-top systems – treat the water at the point of consumption. The former are good for homes that use high volumes of water and want all of it treated, while the latter are better for households that want to treat water for only specific needs, such as drinking.

- Check that the system is certified. NSF/ANSI 42, 53, 55 or 58 ratings means the system has passed the NSF’s stringent testing.

- Don’t forget maintenance. “It’s important to remember that the filter system you select must follow the manufacturer’s guidelines for replacing the filter to ensure they reduce the contaminants of concern”, says Andrews. If you’re not vigilant about maintenance, a filter can become a breeding ground for bacteria.

Want safer water? our handy guide to choosing a filter (click to enlarge):